HOW DAN PRICE BUILT HIS BUSINESS AND FAME ON APPARENT FRAUD

DOCUMENTS SHOW VERY DIFFERENT REALITY THAN price’s favorite ORIGIN STORY

According to an abundance of documentation, Gravity Payments CEO Dan Price purposefully manipulated thousands of client contracts to not only gain an unfair competitive advantage but also swindle millions for personal gain.

Price is the CEO of Gravity Payments, a Seattle-based payment processing firm with satellite offices throughout the U.S. His $70K minimum wage announcement in 2015 ignited a media frenzy. Price became a global celebrity who garnered a hearty endorsement from then presidential candidate Bernie Sanders and high-profile speaking engagements that ranged from The United Nations to Ivy League schools.

Following an 18-month investigation, Hundred Eighty Degrees (HED) alleged that Price concocted the fraudulent scheme as far back as 2003.

Price, his brother Lucas and their father Ron worked as sales agents for a another credit card processor named Axia Payments. According to a lawsuit, the Prices “disclosed confidential and proprietary information and trade secrets by using customer and merchant lists and other confidential information in furtherance of their own interests.”

In other words, Price apparently stole “trade secrets’ and business information for 1,100 clients to launch his own processing business from his dorm room with Lucas. The plaintiff successfully settled the lawsuit in 2004.

Price speaking at the United Nations about fair business and labor practices

Price repeatedly talks about how he fell into credit card processing as a 16-year-old in a rock band that played coffee shops whose owner-operators complained about their payment processing systems.

His origin story awkwardly begs for significant suspension of one’s disbelief. It is hard enough to accept that a mid-teen could understand the complexities of the industry. It is far more implausible, however, that a sophomore in high school be allowed to negotiate rates with billion-dollar banks and card brands.

Nonetheless, Price and brother Lucas established Gravity in 2004. They currently install and supports credit card transaction equipment, enable merchants to process and receive payments and work with banks and credit card companies that require certain transactional fees for processing all the funds through their systems.

Price is supposed to make the lion’s share of his revenue from installations and service, not from minor per-transaction fees.

But Price apparently crafted a way to bury significant sums into his own revenue by fraudulently skimming money from what are supposed to be industry-standard credit card transaction fees.

Former employees with intimate knowledge of the operation advised HED that Price wanted to add as many restaurant clients to his roster as possible. They said 70-80 percent of Gravity's instate (Washington) clients and upwards of 60 percent of out-of-state clients are restaurants.

Before Price can officially onboard a new merchant-client, his underwriting team must properly determine how to most accurately codify the business — restaurant, bar, veterinary clinic, book store, etc.

It’s similar to an insurance underwriter in that the insurance company wants to assess risk before it determines the correct policy valuation. In the credit card processing industry, risk means the likelihood that both the business and the cardholder can pay its bills.

In Price’s line of business, certain merchants are riskier to do business with than others. For instance, restaurants have much larger average tickets than bars. Therefore, when restaurant-goers use credit cards at restaurants, there’s a greater risk that cardholders might not be able to pay off the tab.

Many restaurants include bars. Underwriters must determine if the operation makes more money from food or booze. With restaurants, it’s almost always food. If so, Price must classify them as restaurants.

Credit card companies and banks charge different transaction fees, otherwise known as interchange fees, based on the level of risk they assume. Therefore, restaurant interchange fees would be greater than bar interchange fees.

Price’s underwriters ultimately assign numbers to merchants, otherwise called a Merchant Category Code, so that credit card companies know what interchange fees to apply to that account.

Price should apply the MCC of 5812 to all of his restaurant merchant contracts. Again, this alerts credit card companies such as Visa and MasterCard to apply specific interchange fees that would be higher than fees for bars.

Incidentally, popular restaurants run a lot of tabs. More transactions means more revenue for Price.

As most consumers also know, different credit card types come with different fees for both consumer and merchant, depending on the arrangement with the credit card holder and their Card Issuing Bank — Bank of America, Citi, Capital One, et al.

Every payment processor, including Gravity Payments, pays the same interchange rates which are agreed upon between the credit card brands and the Card Issuing Banks.

HED’s investigation alleged that Price and company knowingly applied the bar MCC to all of his restaurant clients. A seemingly innocuous change from a "2" to a "3" enables Price to game the system without drawing unwanted attention.

He told restaurants he can offer them better rates than competitors. He also told them he would simplify the monthly statements. Restaurants, of course, love the sound of that, because fees can eat into profits.

Most of all, Price could manipulate his contracts so that a portion of fees were directed into his coffers.

Price had been able to execute this alleged swindle without recourse, because he offered clients "flat-rate" pricing. A flat rate combines all credit card processing fees into one monthly rate, thereby hiding how Price manipulated what are supposed to be industry-standard fees.

In other words, unlike nearly all of his competitors, Price's monthly client statements did not reveal how fees were applied to each one of their transactions within a given month.

Price claimed to offer a unique structure to simplify monthly statements for his clients when, in fact, he ostensibly did so to bury traces of fraud.

RELATED STORIES:

WASHINGTON WOMAN FILES POLICE REPORT, SAYS PRICE SQUEEZED HER THROAT AFTER SHE REJECTED SEXUAL ADVANCES… MORE →

SECOND RAPE ALLEGATION AGAINST DAN PRICE … MORE →

DAN PRICE ACCUSED OF RAPE … MORE →

DAN PRICE FACES MORE ABUSE CLAIMS … MORE →

TAMMI KROLL SILENT ABOUT DAN PRICE ABUSE … MORE →

DAN PRICE NDA MUZZLES STAFF … MORE →

DAN PRICE HIRES SEXUAL PREDATOR … MORE →

TWO DOGS DEAD AT DAN PRICE HOUSE … MORE →

DAN PRICE BUSINESS FRAUD … MORE →

DAN PRICE LAWSUITS & LIES … MORE →

DAN PRICE BRIBES MEDIA … MORE →

DAN PRICE AND A BROKEN SYSTEM … MORE →

DAN PRICE ABUSE & FRAUD … MORE →

DAN PRICE VIDEOS … MORE →

A partial list of the news outlets with whom I either spoke or exchanged emails as far back as six years ago, all of whom declined to pick up my reporting, except one nod from Geekwire.

ABC

NBC

CBS

FOX

CNN

MSNBC

The New York Times

The Seattle Times

The Los Angeles Times

The Boston Globe

The Washington Post

USA Today

US News and World Report

Associated Press

New York Post

The New Yorker

Huffington Post (HuffPost)

Idaho Statesman

Idaho Press

Fortune Magazine

Forbes Magazine

Bloomberg

Business Insider

The Atlanta Journal Constitution

The Atlantic

Pro Publica

Inc. Magazine

Entrepreneur Magazine

Southern California News Group (13 publications)

Geekwire

Mashable

Vox

Salon

TruthDig

Plus countless smaller market and smaller circulation outlets

Here is a competitor's transparent statement showing fees per transaction

Here is a Gravity Payments statement without fee explanation - not transparent at all

For the sake of argument, let's say Gravity serves 5,000 restaurant merchants, which is likely a much smaller percentage than the actual number.

Based on data aggregated from markets where Price primarily operates, average restaurant revenue per year transacted via credit cards is $500K. (Price concentrates on higher end restaurant merchants, so that revenue total is likely far more.)

Visa, MasterCard and Discover transactions comprise approximately 70 percent of restaurant card transactions.

$500K x 70 percent = $350K.

The average difference in interchange fees between applying the proper MCC for restaurants or the incorrect MCC for bars is somewhere near .0025 “basis points” per transaction.

$500K x .0025 = $1,250 (what Price scams per year per restaurant, although it is likely far more).

If Price fraudulently codes only 5,000 restaurants x $1,250 = $6,250,ooo per year in fraudulent transactions.

Hundred Eighty Degrees estimates that Price has executed this scam for a at least a decade, probably more, although the number of his restaurant merchants has increased over time.

Therefore, the estimated total of Price's alleged scam over such a period totals between $60-$100 million dollars.

Remember, each and every transaction that a restaurant fraudulently processed because Price purposefully applied the wrong contract code was punishable by significant fines and other penalties which are mentioned below.

HED had compiled a partial list of merchants that it believed Price and Gravity Payments fraudulently coded. HED estimated that the total number of fraudulently classified clients was at least 7,500.

According to research, a considerable portion of these merchants are ethnic in nature, largely Asian and Mexican perhaps portending that a language barrier makes it easier for sales representatives to push a merchant into a fraudulent processing arrangement. It might also be the case that such ethnic restaurants represent a larger market share in regions such as Seattle.

HED eliminated numerous restaurants in markets such as San Diego and Boise in order to determine if they belong on this list.

CLICK to download list

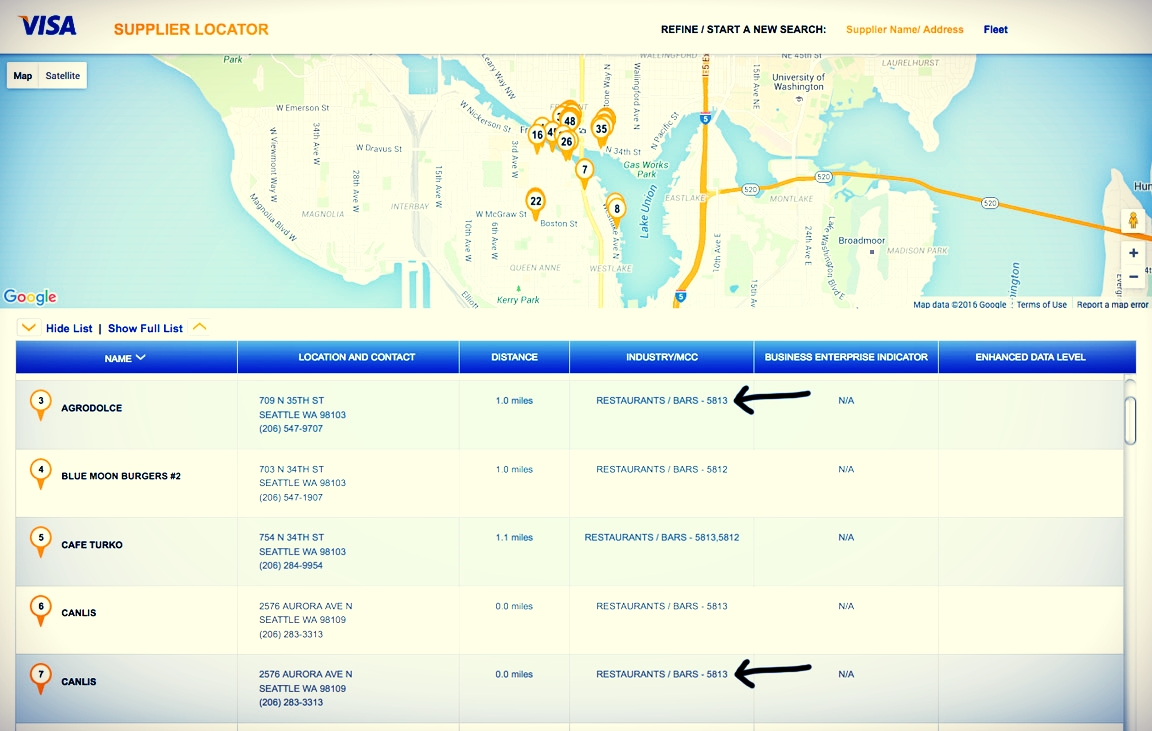

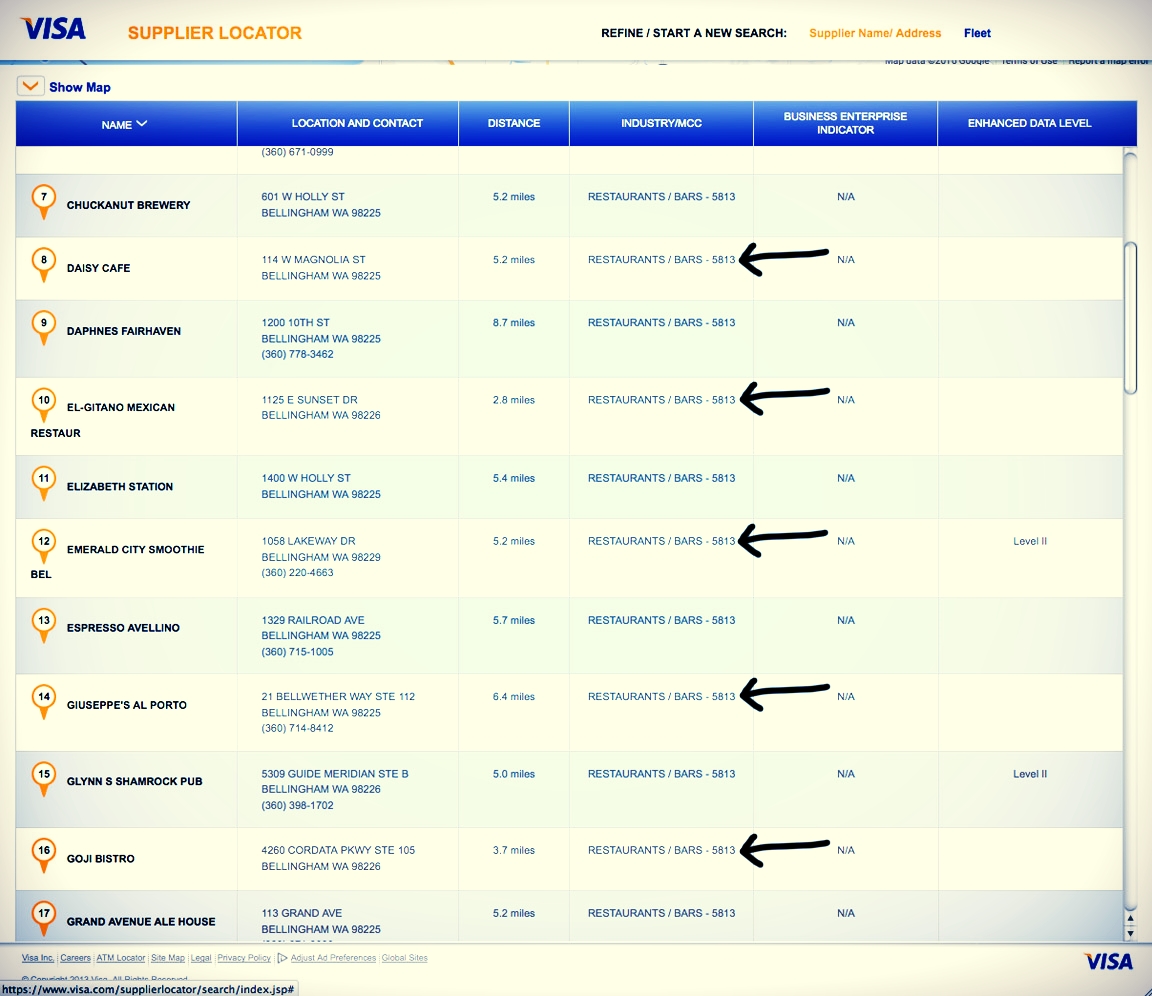

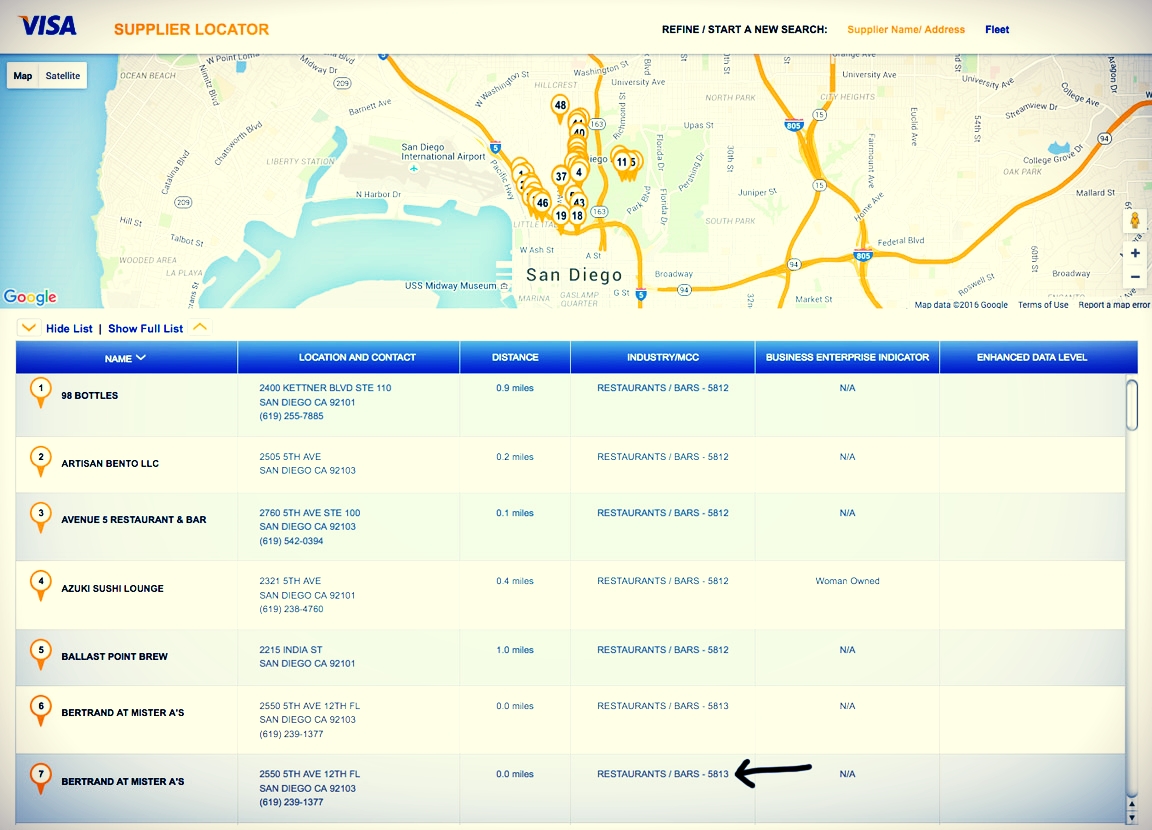

HED released its initial list of clients that Price apparently classified in a fraudulent manner and promptly attempted to contact Visa for comment. Within days, Visa shut down its Visa Supplier Locator tool, the same publicly available tool that HED used to help crosscheck its allegations.

The Supplier Locator is a massive database of merchants who accept Visa throughout the United States. Based on certain criteria selected by users, the Locator unveils merchant contact information, business type and MCC code.

Numerous credit card processors and other parties, including Entrepreneur and Geekwire, corroborated HED’s findings.

Visa refused to comment about why they temporarily shuttered the site.

Below are Visa Locator screenshots of only a handful of merchants that Price fraudulently classified, according to the incorrect MCC codes. These listings should have been coded 5812 for restaurants, not 5813 which is for bars, even though they say “Restaurants/Bars.”

HED originally spoke with the Office Manager of Il Bistro in 2016. His name is being withheld, but he confirmed that Il Bistro is a restaurant, its primary business is food, and he handles the books. At the time of this article, Gravity classified Il Bistro as a bar with a 5813 MCC — refer to the first screenshot of the Visa Locator above.

At some point after HED’s investigation, Either Gravity Payments corrected the MCC to 5812 or Il Bistro contracted with a different payment processor who applied the correct MCC.

Under “Industry/MCC” see the number 5812, which correctly identifies Il Bistro as a restaurant

Andy Ruggles was the General Manager of Agrodolce, a Seattle-based Italian restaurant launched by James Beard Award winner, Maria Hines. Ruggles said, "We've contacted Gravity and are confident that our MCC code is categorized correctly. Dan Price stated to us that any fines or fees regarding this issue would be the responsibility of Gravity Payments and not Agrodolce. "

Apparently, Ruggles only spoke with Price and Gravity, not to an industry authority. However, since HED’s investigation, someone also changed Agrodolce’s MCC to the proper 5812. The restaurant has since closed.

Matt Janke formerly co-owned Seattle's Lecōsho. While Janke had expressed frustration over the manner in which the initial investigation was written, he did, however, request further explanation as to the alleged scheme.

Lecōsho has also since closed.

2021 UPDATE: HED reviewed dozens of the restaurants on its list that had apparently been fraudulently classified as bars. The vast majority were somehow changed to the proper classification.

That means that Price corrected them, the clients left Gravity Payments or Visa alerted Price to properly classify the restaurants or suffer immense penalties. As of this writing, HED does not yet know the answer. But the truth is, the damage was already done and Price had already apparently reaped massive benefits.

Contrary to what Price claims, the following excerpts represent the truth about operating practices, including Merchant Category Codes (MCC), Interchange fees and accountability.

The document known as Visa Core Rules and Visa Product and Service Rules is Visa's manifesto. Where Visa mentions "Acquirer" or "Member," this includes Price/Gravity Payments and, by affiliation, his Acquiring/Sponsor banks, Wells Fargo and formerly BMO Harris Bank.

The above means that Price and Gravity Payments were responsible, not his merchants as he falsely claimed in a Facebook post to follow. And by "staff members," this includes Gravity Payments sales reps, underwriters, finance managers and Price himself.

The above means a Seattle restaurant like Il Bistro, Agrodulce or Canlis must generate more revenue from liquor than from food in order for Price and company to be able to classify them as bars and thereby grant them lower transaction fees. Clearly, this is not the case.

Based on these descriptions, the above means that Price seemed to fraudulently code restaurants as bars. Furthermore, there are plenty of establishments that include the word "bar" or "pub" in their names yet generate more revenue from food than they do from liquor. Those establishments must be classified as 5812/Restaurants. Myriad examples of this are available on the Visa Supplier Locator.

The establishments that HED identified as having been fraudulently coded do not fall into this category. There are, however, approximately 20 that appeared on the Visa Supplier Locator as two separate entries, one as 5812 and a later entry as 5813. A source within the industry has since claimed that such accounts were previously 5812 (Restaurants) but switched to 5813 (Bars) thereafter by Gravity Payments once Price and company outbid their competitors.

The above means that Visa had the right if not responsibility to investigate and audit Price and his Sponsor Banks (Wells Fargo) at any time based on information such as that which HED provided. Though HED had contacted Visa to request any information about an investigation, Visa refused further comment.

The above means that Price and company and his Sponsor Banks must exact due diligence on their merchants, including identifying their primary revenue stream, before they lawfully contract with them. Clearly, this was not the case.

Bullet #5 specifies that the MCC Price and Wells Fargo assigned must be properly supplied to Visa. Clearly, this was not the case.

The above means that Card Issuing Banks should have held Price and Gravity Payments and Wells Fargo accountable for their fraudulent classification of thousands of merchants and thereby demanded reimbursement of all appropriate (interchange) fees that were due them, year over year.

Price began his processing career working as a sales agent for his father. His father's company acted as an independent agent soliciting merchant accounts for a company called Axia Payments. Price apparently breached his contract with Axia by stealing clients in order to start his own processing business. Axia sued and successfully settled. More on this case here.

The above Visa clause essentially stipulates that Price's Sponsor bank, Wells Fargo, should have conducted a background check on sales organizations like Gravity Payments in order to verify its responsibility and principles before entering into an alliance. That does not seem to have been the case.

The above means that Wells Fargo is responsible for ensuring that Price and Gravity Payments operate lawfully and that they too are liable for the transgressions of Price and his team.

Perhaps the above regulation is the most consequential of them all. Were Visa to have held Price and Gravity Payments liable for the alleged fraud that he peddled through unsuspecting merchants, the credit card companies can also hold those same merchants liable to the tune of millions of dollars, depending upon how long they have been Gravity clients.

This regulation stipulates "...receiving an inappropriate Interchange Reimbursement Fee," meaning that each fraudulently processed transaction is subject to the above fines, not to mention other penalties such as being forever banned from processing credit cards.

Incidentally, come tax time, Gravity Payments restaurant merchants receive a document called a 1099-K. The form is actually sent by First Data Corporation, a Gravity financial alliance. The 1099-K is an IRS information return used to report certain payment transactions to improve voluntary tax compliance. First Data sends the 1099K on behalf of Gravity after which Gravity's merchants verify and account for their credit card income to ensure that the proper tax is paid.

They key here is that front and center on the form are two boxes that show, 1.) the Merchant Category code, and 2.) who the payment processor is. Therefore, every Gravity restaurant merchant can see if it is fraudulently coded. Here is such an example:

Were the Credit Care Card Brands and Card Issuing Banks to retroactively and successfully prove that Price and his merchants perpetrated fraud, penalties would pile to the clouds and violators would find it nearly impossible to keep their lights on. Here are Visa's very own violation clauses:

HED spoke with a former Gravity sales rep, Sean Ring, who sold in the San Diego market. Gravity was a place where Ring could cut his teeth in outside sales. He worked in hospitality for some years before joining Price’s team, and this is likely why Price hired him to woo high-ticket restaurants.

Ring said the cold-calling and utter isolation got the best of him in the end, He said that Price was constantly, if not even harshly, on his reps to emphasize how transparent Price was with small business merchants. Regardless, Ring said of Price and Gravity that some things never quite added up:

“Somehow we were able to set up restaurants at below cost. I couldn't understand it, how we could get accounts set up that way. There was a focus on restaurants with higher average tickets and it had something to do with the bars, I couldn’t figure it out. I would get these contracts back from underwriting with an incredibly low flat rate and it was never explained. I thought Dan had some inside track to something. There was always something with Dan I could not put my finger on. I had to walk around with articles with Dan’s face on them and staple my business card to them, like he was some kind of celebrity. I texted him after the wage hike [two years after he left the company] to congratulate him, and he texted me back to see if I now wanted the job back due to all the publicity. I called a friend I had made at Gravity who still worked there, and when I mentioned the media attention Price was getting she said all of it made her want to vomit in her mouth.”

HED also spoke with Brian Bell, a 22-year veteran sales rep for payment processor, PayPros. He knew Ring and had nice things to say about him, despite the fact that Ring and Gravity swiped key restaurant accounts away from him; accounts that Bell had for years. In fact, Bell also spent 16 years in the hospitality industry prior to PayPros — he clearly knows his way around a restaurant operation. After losing business to Price, Bell decided to determine how it was possible:

“Gravity beat me on pricing by a bunch, and that was just my basic pass-through cost, not cost-plus. So, I did a full year of interchange research on Bertrand at Mr. A’s, one of the restaurants I lost to them. I determined the only way they could do what they were doing was by miscoding a 5812 to 5813. The difference on interchange was $5,000 from only one restaurant in one year.”

Bob Carr grew Heartland Payment Systems from two-dozen employees in 1997 to 4,500 today. Carr sold Heartland to Global Payments for a whopping $4.3 billion dollars. Until Price grabbed the spotlight, Carr was the most high-profile figure in the credit card processing arena with friends in very high places. In fact, then President Obama appointed to a special infrastructure committee.

In 2008, Heartland suffered what is widely considered one of the largest data breaches in U.S. history, compromising data of up to 100 million credit and debit cards issued by more than 650 financial services companies. Heartland rebounded and used the debacle to pioneer new encryption and security measures, though they were breached yet again in 2015.

Regardless, Carr was known as an ethics champion accused of summoning government over-regulation after he penned an open letter that strafed the very industry that made him extremely wealthy.

In the letter, Carr “called out criminal and misleading practices” including “deliberately misrepresenting MCC codes" and "some of those benefiting from bad behaviors look the other way and attack the messenger in the ultimate act of intellectual dishonesty.” Carr told HED:

“Deceptive trade practices have no place in this industry, period, and we must be committed to doing everything and anything we can to end junk fees and intimidation of merchants. It is really impossible to know if an investigation [of Price] is ongoing or not. Our industry is dominated by financial engineers with few, if any, concerns for normal people.”

Kacie Long worked as a sales rep for Heartland. She operated out of Boise, Idaho, not far from where Price grew up. Though Long is familiar with Price, she would not comment on the record about his exploits. She did volunteer:

“The underwriting and contract process is black and white. It is absolutely clear how all of us must classify a business such as a restaurant. Card brands can audit at any time. I would never put my customers, who place a lot of trust in me, or my company in that position.”

Tim Murry is a partner at SMARTMerchantsClub, a Seattle-based processor. He shared this with HED:

"When an agent in our industry sees a statement that is blank except for a flat rate, the first thing we think is what are they hiding? A flat rate means there is no way to see what the processor is hiding because the Visa and MasterCard interchange is missing, no way to see if their processor is correctly paying their Visa and MasterCard fees. It’s so hard to explain that what they think is a simple flat rate is most likely a tactic using their trust as a tool to defraud Visa and MasterCard. And worse yet, the poor merchant doesn’t even know and could be liable for the fines from the card brands and perhaps make them pay back the interchange, although more likely the processor who is responsible for insuring the accuracy of a MCC code is more apt to receive the penalties, which would be substantial. We could lose our right to operate in the industry if we purposely miscoded merchants. Your [Hundred Eighty Degrees] discovering the MCC codes online was quite resourceful, and had other processors known this was there, they would likely turn in competitors reporting wrong codes. Any merchant on a flat rate should demand to see a copy of their monthly interchange breakdown from the card brands going back several months, if not longer. We care about our merchants too much to put them in this risky situation of miscoding them for our profit or to unfairly compete."

Price’s process was a bit confusing for Brian Canlis who co-owns and operates Canlis, a 60-year-old, James Beard nominated, high-ticket Seattle eatery. Canlis signed on with Price over a decade ago.

When New York Times reporter Patricia Cohen interviewed Canlis, she said Canlis “was more discomfited by his [Price’s] actions” and that he though the pay raise at Gravity “makes it harder for the rest of us.” Nonetheless, Canlis remained a Gravity merchant. Canlis said:

“We feel the same today as we did when Dan first made his announcement – completely supportive. We were never worried about increased fees - Gravity assured us there was nothing to worry about. We've been a client of theirs for over a decade… We frequently field phone calls from credit card processors trying to get our business. None of them have been able to match Gravity's rates.”

HED shared its findings with Canlis who said, “Wow. A little in shock right now. And if what you're writing is true, then I'm glad you wrote it. We work so hard to do things the right away. I have many phone calls to make. Thanks for giving me a heads up on the article.”

Per the current Visa Locator, Canlis is still classified as a bar, not a restaurant.

Ethan Stowell Restaurants is a nationally recognized group of esteemed operations that had also been one of Price's early adopters. Sources said that Stowell apparently abandoned Gravity because of these business practices.

Reports from industry sources reveal that other restaurant operators followed suit.

Even if restaurant merchants were unaware of Price’s dodge, they could still be financially or logistically inconvenienced in any number of ways. Card brands and banks could audit them. Liquor control boards could investigate whether business licenses do not match the business model classification and levy fines or other punishment.

And even Price himself can push the blame upon them. In fact, he proved willing to do so. Price learned about HED findings and, within the week, released a Facebook post that did not mention HED by name but addressed the allegations.

He stated that restaurant merchants are responsible for classifying their own businesses. This is not only untrue, it is a direct violation of Visa's rules. This was clearly a tactic to shift accountability to his very own merchants with whom he fervently claimed to share an inimitable trust.

Price crafted this explanation as if he had nothing to do with the alleged fraud. He also explains the process as if the merchant should know about it, when it is the sole responsibility of Price and Gravity to do what is right and just. When he writes, “We also generally do a site inspection to make sure the merchant’s stated category code makes sense,” he is either lying or he is essentially admitting that he thereafter fraudulently codes his restaurant merchants.

In yet another curious act, Price also took to Twitter that very same day to defend himself against HED allegations. His reply:

HED sought comments from credit card brands, card issuing banks, Price's sponsor banks Wells Fargo and formerly BMO Harris Bank and also First Data Corporation.

Wells Fargo is, "federally insured financial institutions responsible for connecting merchants to Visa Inc. and MasterCard Worldwide authorization and settlement systems.... also called an acquiring bank, merchant bank or sponsor bank."

In other words, because Gravity Payments is not itself a bank, Price must establish a strategic alliance with these banking institutions in order to process payments through the financial system. Explaining the system can be a somewhat wonky exercise.

Other than a few boilerplate statements, banks and credit card companies have refused to comment on HED questions. It remains unknown as to whether any of these entities investigated Price after HED made them aware of its findings.

HED asked Wells Fargo representative Jim Seitz the following questions:

Is an Independent Sales Organization (ISO) like Gravity subject to periodic audits by Wells similar to how other sponsor banks audit their ISOs?

When was the last time you audited Price? Or have you ever?

Are you currently conducting an investigation on Price or Gravity?

Are you aware how Price is classifying his restaurant merchant contracts and thereby leveraging his/your merchant accounts in order to apparently process fraudulent transactions?

Since Price seems to process fraudulent contracts in order to gain an unfair competitive advantage, gain more merchant accounts, and short credit card Issuing Banks of their proper fees, what kind of penalties or processes would/will Wells apply?

The dollar amount of alleged fraudulent transactions is, on the low end, tens of millions of dollars, and on the high end, well over $100 million dollars.

Price never advised restaurant merchants that they were classified as bars which thereby placed them in an an unsuspecting role to fraudulently process lower credit card rates and carry out Price's scheme.

Price's scheme could force restaurant merchants to be held liable for fraud up to $10K per transaction per month, year over year, as well as other penalties that preclude them from processing credit cards in the future.

Price placed his sales and underwriting teams in legal jeopardy by orchestrating his scheme.

Price claims to be "the most trusted" small business processor that offers full transparency and simplicity. However, he fails to to disclose vital if not standard information on merchant statements in order to hide his scheme.

Card brands, card issuing and acquiring banks and Prices' sponsor bank partners, such as Wells Fargo and First Data Corporation, should regularly audit processor practices and actively prosecute or penalize wrongdoing. They apparently did not do so.

The IRS and local and national liquor boards should levy fines and penalties for wrongdoing. They apparently did not do so.

Seitz offered only a boilerplate response:

"Wells Fargo sponsors a number of Independent Sales Organizations (ISOs), such as Gravity Payments. Organizations that are registered ISOs of Wells Fargo are able to access the Visa and MasterCard payment networks and offer payment processing to their customers through our sponsorship. The sponsorship of ISOs is a standard practice within the payments processing industry. Well Fargo informs and requires its ISOs to abide by payment network rules.We have extensive procedures in place to ensure third-party processors and independent sales organizations (ISOs) comply with our policies and payment network rules, yet we do not discuss our practices and procedures in detail. Due to customer confidentiality, we cannot provide further comment."

HED called and emailed Price's other former Sponsor/Acquiring Bank, BMO Harris. No reply.

HED spoke with First Data Corporation representative Hally Sheldon who said she would share my requests with her team and issue a response. No reply.

HED exchanged emails with Jason Oxman, former CEO of the Electronic Transactions Association (ETA) "the international trade association serving the needs of organizations offering payment technology products/services." ETA is one the industry's leading policy and advocacy voices. The questions:

As the self-described "principal representative of the industry" please advise how processors who do effect fraud should be handled by Issuers, Card Associations, federal authorities and/or the ETA, especially since you "advance the technology, safety and security of payments every day."

ETA's "Voice of Payments" platform is the self-described "leading source of credible industry information for government officials making legislative and regulatory decisions impacting our industry." Since this is the case, what responsibility do you and the ETA have to inform and convince such stakeholders that a processor like Gravity Payments is an anomaly and that the industry is well-policed from the inside and the outside?

The ETA published a white paper titled "A Practical Approach to Acquiring Risk Management." It's downloadable from your site. An entry on page six reads, "External Fraud Risk: The risk that an unauthorized entity/individual(s) commits fraud against the company or uses the company system to commit fraud. This includes compromised merchant or reseller accounts, theft of card account numbers, bank account numbers, or other sensitive information; extortion, theft of intellectual capital, etc." How does a merchant protect itself from the external risk of a payment processor who leverages said merchant to exact fraud?

Though Oxman is able to answer such questions beyond the context of Gravity Payments, he responded accordingly:

You originally asked me to comment on your investigation of Gravity based on your assumption that Gravity was an ETA member and therefore we would have familiarity with the company. I responded that Gravity is in fact not an ETA member and that we have no comment. You are now asking me additional questions, and having had the benefit of reading your article, I know that all of your questions are still asked in the context of Gravity. Thus we still have no comment. I understand you are pressed for time as you are publishing today, and I appreciate your reaching out to us.

JDO

The Strawhecker Group is a leading management consulting company for the payments Industry. TSG clients include merchant acquirers/ISOs (like Gravity Payments), issuers (like Bank of America, Capitol One, Citigroup, etc.), the card brands, technology and mobile companies, processors, major merchants, bank specialty lenders and private equity firms, as well as banks and financial institutions.

HED interviewed Founder and principal Jamie Savant for the initial investigation about Price and about industry standards and practices. This was Savant's response to a request for follow-up comments regarding the now released investigation.

Hi Doug,

I am on back to back calls today, sorry

Jamie

No further reply.

HED left numerous messages for Visa's former Senior Director of Global Corporate Relations Sandra Chu and others. No reply.

Processing companies and independent sales organizations across the country said to HED that they are paying close attention to the way Wells Fargo, First Data, the card brands, merchant/acquiring banks industry authorities and gatekeepers are handling this matter. If widespread fraud is substantiated, Price and Gravity are on the hook for enormous fines and other penalties that yield potentially lethal consequences for his operation.

According to card brand rules, Price's restaurant merchants are also potentially on the hook with the same consequences in tow. However, if no further action were exacted upon Price or Gravity, a number of processors with whom HED has had extensive interviews and who are industry heavyweights, have stated that they will voice hearty and sustained disapproval over inaction.

Some have gone so far to say that such inaction may very well invite even further violations of the same manner.

HED has not heard of or witnessed any further action.

Price can very simply evade further scrutiny over alleged fraud. He can change the erroneous MCC codes of to the proper designations for all of his restaurants and he can do so at any time or contimue taking the risk. Changes can take as little as 24 hours if authorities come knocking.

HED is not yet aware of whether he has manipulated the accounts. In doing so, Price would upend his scheme and not only force merchants to pay greater fees but also preclude him from unlawfully skimming off the top.

Again, processors like Price and their sponsor banks are ultimately responsible for providing correct information to card associations.

Willful fraud is especially dispiriting to hardworking restaurant owner-managers. All a processor has to do is properly process its merchants in the first place and practice what they preach in terms of transparency. Credit card processing itself is not the culprit. It is both a complex and critical component of every local, regional or international consumer-facing enterprise.

Price has deployed eerily similar "victim" language for a long time, primarily in the context of how he somehow never has an idea of how he may exploit people or processes.

Here are just a handful of the many examples of this canned routine...

Speech at his alma mater, Seattle Pacific University, go to 11:07... https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-slGSPkzbVQ

Interview with Inc. Magazine, 7th paragraph... http://www.inc.com/jon-fine/dan-price-speaks-at-vision-2020.html?cid=sf01001&sr_share=twitter

Keynote speech at the Inc. 500 conference, go to 10:30... https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BKM9lpuUN58

When Price spoke at the United Nations, he opened with a statement about how he had beer the night before and how he is getting so old that he could feel the beer he had last night.

He subsequently explained how his company is famous because he offered a minimum pay rate of $70,000 that “we're working toward.”

Deeper into his speech, Price said what he and his reps have perhaps said to restaurant merchants for more than a decade. "The other thing I thought about as a leader is, it's really hard to get people to tell you the truth."