Law & Disorder

By Michael Nigro | All photos © Michael Nigro

Activist Sarah Wellington of the activist/art collective We Will Not Be Silent, at an Eric Garner memorial, NYC 2015

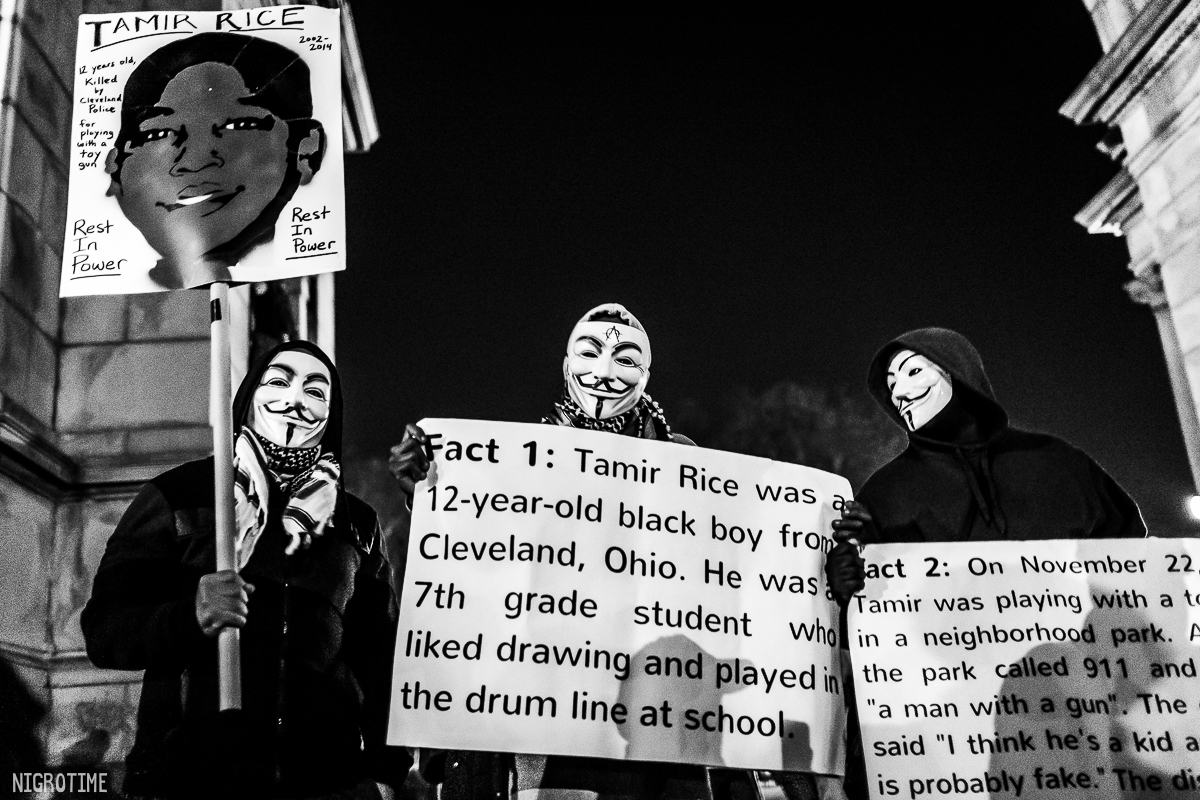

During the Tamir Rice protest in downtown Cleveland, on December 29, 2015, police officer Brian Dorin, after using his cop car to "win" a game-of-chicken versus street protesters, rolled down his window and yelled at a 25-year-old black student-activist, "Do you want to be the next one."

The incident is recounted in my Huffington photo essay published on January 8, 2016.

Alana Belle, the student-activist to whom the phrase was directed, has now filed a complaint against Officer Dorin through the Office of Professional Standards (OPS), a civilian run police review board.

The Cleveland Police Department (CPD) has also begun their own separate investigation and has assigned their Internal Affairs division to evaluate the incident.

That's good news. And a rational response. A member of the public is filing a complaint against a public servant and is told that her request will be honored.

In a recent phone conversation with Belle, however, she says that since she began the process of filing a formal complaint, the police have, at least six times, followed her when she leaves her home, work, or from her evening writer's workshop.

She also said that during subsequent Tamir Rice protests, legal observers from the National Lawyer's Guild and other activists revealed to her that the police are singling her out as one of "the leaders" and, during the protests, closely monitor her.

As I had witnessed the incident on December 29, I know that the truth is on Belle's side. It's a powerful place from which to argue, except when you're speaking truth to power. And the police are a powerful force.

The Rev. Bruce Lambert Butcher of St. Paul A.M.E. Church

What little has come to light with the on-going investigation suggests a degree of spin from the CPD, setting up a rote police narrative whose outcome is a fait accompi.

The responses from Steve Loomis, president of the Cleveland Police Patrolmen's Association (CPPA) in a January 15 Cleveland.com follow up piece, is typical, if not predictable. Criminalize dissent, launch ad hominem attacks and threaten legal action against Belle.

Alana Belle is a citizen who has asked for a public servant's behavior to be investigated. That's it. That's all.

When asked over the phone if she was looking for remuneration, Belle said, "No. Absolutely not."

Yet because of the nature of her complaint, rather than pursue the investigation objectively, it seems that the CPD would rather obfuscate, and employ the tactic of trying to make Belle look like an angry black woman, who deserves it.

Due diligence and unbiased investigation can reveal the truth. This is one of the reasons why Cleveland's Mayor Frank Jackson pushed for the Department of Justice (DOJ) to investigate the Police Department in March 2013.

In fact, in May of 2015, the City entered into a court enforceable agreement with the DOJ to address and investigate the CPD's pattern and practice of excessive force.

A Monitoring Team is currently overseeing the Cleveland Police Department's compliance with the U.S. Department of Justice consent decree.

Matthew Barge, one of the 15 Monitoring Team members, said in a phone conversation that they are aware of the Belle/Dorin incident from members of the public.

"The Monitoring Team is not in the position to actually run the investigation in the department," Barge said, "We're there to make sure that the investigation is fair and accurate."

Barge went on to say that Charles See, the Director of Community Engagement for the Monitoring Team, was there the night of the incident, but did not observe it.

"He was dispatched to the protests to observe and get a sense with his own eyes what was going on," Barge said.

Charles See (far right) Director of Community Engagement observing the protest on December 29, 2015

But the police want video. I get it. It's smart. It protects all sides. But they want it from Belle, who has yet to obtain any video or audio from protesters who were there that evening.

Cleveland.com's request for Officer Dorin's body camera footage from the city was denied. The Cleveland records department rejected their request citing the Confidential Law Enforcement Investigatory Record exemption, or CLEIR, an Ohio statute under the Public Records Act.

The records custodian wrote in an email to Cleveland.com, "That the video is part of an ongoing investigation and not releasable at this time based on [CLEIR] the confidential law enforcement investigatory record exception [sic].'"

Law enforcement and City Officials use CLEIR time and again to keep public records from, well, the public.

More on CLEIR shortly.

The author of the Cleveland.com piece, Ryllie Danylko, erroneously quoted my Huffington Post article by stating "Nigro saw Officer Dorin turn on his body camera during the first encounter with Belle."

I never wrote that. I never saw that. I wouldn't even know the physical action it would take to turn an officer's body camera on.

What I did write, however, in my first-person account, was this: "Officer Dorin then decided to aim his body camera (as seen in the photo below) and record us. Good. I'd love to see if he even turned it on."

Officer Dorin pointing his body camera

Which brings us to the verbiage of the city's records department that was sent in an email to Cleveland.com: "the video is not releasable at this time."

These words all but confirm that Officer Dorin did, in fact, have the body camera on. Zooming in on the photograph reveals the tally light on the body camera is illuminated.

So, back to CLEIR and the city's records department refusing to release the body camera footage.

According to attorney Jack Greiner at the Graydon Head Law Firm in Cincinnati, who is one of the leading advocates for public transparency in the state, and has argued numerous cases involving CLEIR exemptions, it appears that CLEIR does not apply in this particular investigation.

On a phone call, Greiner said, "Based on your description of the incident, the assumption is that Officer Dorin was on site during the protest to observe and manage the action."

Greiner went on to say:

"If there was no criminal investigation at the time of the incident, CLEIR does not apply. The body camera footage precedes the actual investigation. In fact, you don't even need to be concerned with any of the CLEIR exemptions, if there was no investigation at the time. It's the equivalent to a 911 call."

When asked for the official reason why Officer Dorin was on site during the December 29th protest, Dan Willams, Media Relations Director for the City of Cleveland wrote in an email, "This is an on-going investigation so when it is complete we will be able to share more details."

If Dorin was at the protest to protect and serve, to monitor, and was not there as part of an active investigation, then the body/dash camera footage should be made public.

Moments after saying, "You want to be the next one" to Alana Belle, Officer Brian Dorin repositioned his vehicle.

If history is any barometer, however, more than likely the public will never see it. The reason is not exclusive to Cleveland. Commandeering and impeding the release of police video is a nationwide struggle.

Just look at Chicago. It took a year to get the Chicago police to release the video of the October 2014 murder of Laquan McDonald. The video exposed the official police narrative as a lie.

And then last week, again in Chicago, a Federal Judge forced the release of yet another video, this time from 2013, of the fatal shooting of 17-year-old Cedric Chatman. The police narrative was fiction.

Police not releasing video happens with such frequency that it's par for the putt-putt course; law enforcement's propensity to protect their own, rather than the public they have sworn to protect is disheartening at best, an institutionalized public danger at worst.

There are dozens of instances of body camera footage countering official police narratives (and, to be fair, there are dozens of instances exonerating police, too). But why the double standard of who gets access? They are public records.

Just this past week, it was reported that The New York Police Department is asking for a $36,000 "copy fee" to anyone requesting the release of an officer's body camera footage. Who, besides terrorist organizations, extorts money and holds other people's lives in their hands for what is ostensibly a ransom fee?

Loomis, the CPPA president, said in a statement to Cleveland.com, "Just because [Belle] said it doesn't mean it's true. Protesters say a lot of things."

Even if you don't frame the above statement with the understanding that police are given an expansive breadth to lie to get information and/or entrap people, one must logically recognize that the opposite to Loomis' statement holds as much weight. Just because you deny it, doesn't mean it didn't happen.

Have we somehow lost the capacity to understand that an event can indeed occur even if it's not on video? There are eye-(and ear)-witnesses to corroborate Belle's story. I am one of them.

I have covered dozens and dozens of protests, from individual acts of civil disobedience to marches of over 400,000, and I simply cannot get my head around Loomis' claim in Cleveland.com where he states, "Literally every inch and every second of those protests are videotaped by someone."

This, literally, is not true. Not even the small scale actions can lay claim to having every inch and every second video taped.

But words have meaning. Literally. As do the words I write here. As do the words from the Cleveland public records keeper. As do the words Officer Brian Dorin said to Alana Belle.

So let's take Officer Loomis' claim, his words, as truth, that every inch and every second of that protest is video taped. He said it. He now has to own it. Just as Alana Belle is owning her statement.

Therefore, there should be over four hours of footage of me walking through downtown, taking over 700 pictures, interviewing and meeting people, standing in front Officer Dorin's car as he bumper-bullies forward, screaming my lungs out at him after he asked Alana if she wanted to be the next one, of me leaning right up against his window demanding his name and subsequently giving him my protected-by-free-speech finger when he wouldn't divulge it.

There should also be over 6 hours of footage of Alana Belle, every second and every moment that she was protesting that day.

But it doesn't exist. And guess what else doesn't exits? Seemingly a vote from the grand jury.

Just prior to publication, Cleveland Scene: reported that the Grand Jury in the Tamir Rice case never actually voted on the charges, which included aggravated murder, against the Cleveland police officers Timothy Loehmann and Frank Garmback.

Cleveland.com: would later clarify the procedural nuances of the grand jury, and quoted the Rice's family legal team: "The prosecutor saw to it that the grand jury never took an up-or-down vote on specific criminal charges..." The Rice family followed up in a press release/petition that stated, "It's time for the Department of Justice to investigate Tamir's killing and the investigation and grand jury process that followed."

We need to remember why this conversation is even happening. A 12-year-old boy named Tamir Rice is dead. And he shouldn't be. And no one is accountable. That's what this is about.

His death has motivated citizens across the country, including Alana Belle, to speak out and attempt to stop the next one from ever happening again. Literally.