Will Pasadena Unified Learn Its Own Lesson?

Pasadena Unified School District board meeting September 27 (Photo/Forbes)

PASADENA, Calif. — Members of the Pasadena Board of Education said during Thursday’s meeting that they were still concerned about vacant teacher positions and unavailable instructional materials, despite having voted 5-1 to drastically reduce spending eight months before.

On February 8, the board unanimously voted to eliminate 139 full-time positions in the Pasadena Unified School District (PUSD) — including 87 teachers and two assistant principals — by the end of 2019.

A special joint meeting of the board and city council followed on February 15, at which time PUSD Superintendent Brian McDonald blamed budget woes on increases in pension and health care costs, underfunded but federally mandated Special Education initiatives and declining school enrollment.

During Thursday’s meeting, District 7 board member Scott Phelps said to fellow members, “The board talked about this on a recent retreat – that we want to have a goal to open the year fully staffed in teachers and in materials provided to all. Does everybody still feel that way as a goal?”

District 1 board member Kenne, who struck the only “no” vote on February’s budget motion, said, “I definitely wanted trained, certificated teachers in every classroom, with materials that teach our students from day one.”

Kenne said that, following five years of unsuccessful attempts to have school administrators provide annual rollout plans for curriculum and instructional materials, not only does she have “low expectations,” she is also concerned that remaining teachers are not given the time, training or pay to adequately adapt to new demands.

Interim Chief Business Officer Eva Lueck said during Thursday’s meeting that for the current fiscal year, PUSD is “in great shape.” But she said “in future years, not so good.”

Lueck said that the district is currently solvent solely due to the combination of a $5.5 million one-time grant and elimination of certificated (teacher) and classified (clerical and custodial) positions.

The board and local reporters have made numerous requests for current lists of K-12 vacancies, substitutes and shortages of materials for the 2018-2019 school year. District human resources representatives and the superintendent’s office have yet to provide such documentation.

According to a year-old post that remains on the PUSD website, “With the prospect of more than $13 million in budget reductions over the next two years, PUSD is fundamentally changing its planning and budget development process to focus on the instructional core - the essential interaction between teacher, student and content that creates the basis of learning.”

Focusing on that “instructional core,” however, requires proper teacher training and materials for which the district has struggled to identify future funding.

Lawrence Torres is PUSD board president and a career educator who, for more than 25 years, has worked at City of Angels School in Los Angeles, an alternative K-12 program.

“We’re in charge of people’s most precious cargo. But then you also have to deal with the professional accountability piece of this.”

Torres said they need to make serious cuts, but “that conversation really ticks me off, especially when you have to decide between instructional aids and librarians.”

During the 2017-2018 school year, PUSD lost roughly 400 students to other districts and private schools, Torres said, and since each student represents $12,000-$14,000 in state funding, the district lost millions of dollars in revenue.

According to the “Student Population Forecast” by Davis Demographics & Planning, Inc. — a third party contractor providing school planning and geographic information system technology to K-12 districts in 44 states — PUSD enrollment has declined by approximately 1,500 students since 2012.

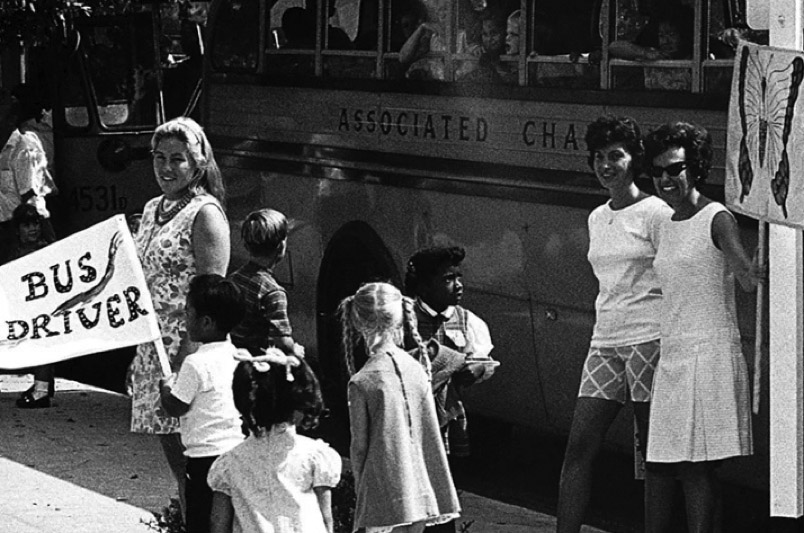

When Pasadena became the first non-Southern city federally ordered to integrate its school district in 1970, racial polarization spawned white families with enough means to leave or send their children to private schools.

Pasadena busing after desegregation mandate in 1970 (Photo/Unknown)

According to Town Charts — a data aggregator for every location in the U.S. — of all current PUSD eligible students, only 55 percent attend district schools, while 45 percent opt for one of the 53 local private institutions. This public school nonattendance ratio is three times the national average.

State support for California’s public school districts is largely tied to Proposition 98, which in 1988 established a minimum level of funding based on enrollment and average daily attendance (ADA). Funding must be solely used for instructional improvement and accountability.

Helen Hill is a former Pasadena public school teacher and current Director of Curriculum, Instruction and Professional Development for PUSD. She said that while she is proud of the district’s inclusive process in developing resources for the classroom, the amount of time to ultimately support teachers is now vastly depleted.

“We have massive teacher staffing issues, battles with our unions and tentative financial structures. Our curriculum is the bare minimum and on its own won’t be enough.”

Hill said that adopting the state’s recommended math framework alone cost $1.3 million. She said the district only serves certain portions of its kids well, but support of English language learners and students with developmental or physical challenges remains deficient.

PUSD is a 27-school district with approximately 17,000 students, 84 percent of whom are nonwhite, 65 percent economically disadvantaged and 19 percent English learners. The district’s 24:1 student-teacher ratio is well above the national average of 16:1.

In 2012, California adopted Common Core standards — anchored in “critical-thinking, problem-solving and analytical skills” — to help students of all stripes better prepare for college and careers.

Based on those standards, the California State Board of Education (SBE) evaluates and adopts individual subject “frameworks” every eight years and submits its recommendations to local districts such as PUSD.

Though math and English language arts are the two subjects tested statewide, the CDE supports other content areas such as history and social studies.

Dr. Stephanie Gregson is director of the Curriculum Frameworks and Instructional Resources Division at the California Department of Education and executive director of the Instructional Quality Commission.

Asked about the lengthy eight-year span before single-subject frameworks are updated, Gregson said, “I wrestle with this a lot as a former teacher and now being in a position where I manage an adoption process with budget restrictions.”

Gregson said there is always room for improvement, but with the most school districts nationwide (1,000), California had to establish itself as a Local Control State. Under this model, the CDE makes curriculum recommendations, but districts inject their own pedagogy through a Local Control and Accountability Plan.

Julianne Reynoso is an assistant superintendent for PUSD elementary schools and a career educator. “What we are using to teach does not actually matter as much as the pedagogical approach itself — how and why we are teaching in a certain manner,” she said.

Reynoso said the district does not have enough money to execute in the classroom the way it planned. As an example, the state’s newly adopted social studies framework will be difficult if not impossible to afford, she said.

“Because of financial constraints, we need to be much smarter about projecting our needs into the future and bridging that to our investments.”

Christine McLaughlin has taught sixth and seventh grade Honors English at Blair High School for a decade. “I was proud of PUSD for being ahead of the Common Core adoption process,” she said.

Blair High School, Pasadena, California (Photo/Forbes)

McLaughlin said the district treats teachers as subject matter experts and involves them in critical curriculum decisions, but yet she has to “beg, borrow and steal” books to supplement texts that have been around for years.

“The system is wonky,” she said. “We were told by curriculum people we would get 300-400 books this year and last year to support our Balanced Literacy program. But after last year’s spending freeze, we’re still waiting.”

Emily Mencken has a daughter who attends eighth grade at Blair High School and twins who attend fourth grade at San Rafael Elementary School. She is the former executive director of Cottage Co-op pre-school and current board member of Pasadena Education Network (PEN), a decade-old nonprofit that promotes family involvement in Pasadena’s public education system.

“I tend to stay out of the (curriculum) implementation process and am more inclined toward evaluating the long-term plan,” she said. “The district does a pretty poor job at communicating with parents.”

Mencken said she knows of high school classes that did not receive new texts for the beginning of the school year as planned. “We have kids sitting in classrooms with outdated materials. If we don’t have money, curriculum does not matter.”

Jo Mann has a son who attends fifth grade at Hamilton Elementary School. She said the district emphasizes English language arts and math to the detriment of everything else. “Overall, I think the curriculum is pretty limited and does not seem to allow for much creativity from the teacher or the student.”

Jo Mann, parent of PUSD elementary school student (Photo / Jo Mann)

Mann said her son’s education is “not terribly progressive,” and it does not relate to the present or future lives of the kids as much as it could, so they lose interest.

She said she is frustrated by the lack of resources, and teachers not instructing to the individual.

“My son meets or exceeds state standards, but where's the challenge? Where's the next level?”

The PUSD superintendent’s budget advisory committee said that PUSD must develop “greater accountability for spending” to maximize resources while prioritizing continuous improvement in academics and increasing socioeconomic integration.

In 2000, Proposition 20, known as the “Cardenas Textbook Act of 2000,” provided that one half of state growth in lottery funds for education is allocated to school districts for the purchase of instructional materials.

During the 2017-2018, PUSD received nearly $4 million in lottery-related funding, ranking 15th statewide out of nearly 600 eligible recipients.

On the Nov. 6 ballot, city residents voted “yes” on Measures I and J, which will increase the city’s sales tax from 9.5 percent to 10.25 percent, the peak rate in California. It remains unclear as to whether the Pasadena City Council will keeps its pledge to earmark a portion of that funding for debt offsets and to avoid a potential takeover by the Los Angeles Unified School District.